For thou art man and not God, thou art flesh and not of angels. How couldst thou remain forever in this state of grace being neither an angel in heaven nor the first man in Paradise? I am He who comforteth the downcast with gladness.

From the third book of Rhenish traveler THOMAS à KEMPIS (1379 – 1471)

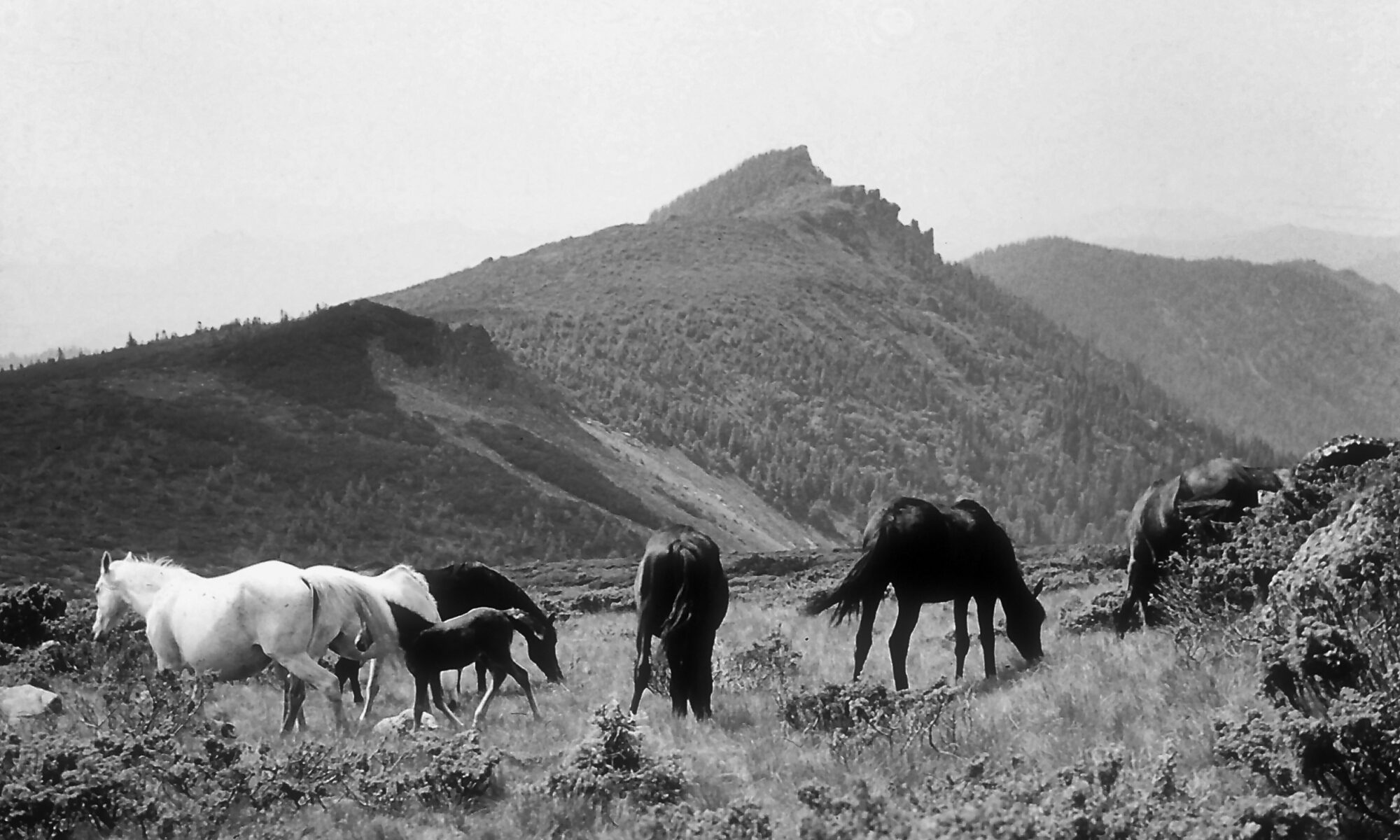

That day is sure to come, as unexpectedly as a lone swan appearing upon the northern horizon. Rare, snowy white, it flaps its wings slowly – far has it yet fly. An other-worldly day, unburdened by time. The longer you sweat and toil beneath the weight of time, the greater the certainty that the day will soon arrive. Days when I feel the ponderousness of time and my own diminishing vigor are days when I strain and struggle. Time and a stallion’s strength are the hounds that drive me. I feel I must see everything, climb each craggy slope, ford each rushing river, explore each winding valley, and record it all in my memory. I trudge arduously through the mountains. The joy I feel is not silent and knowing, but fierce and animal. On such days, I yearn to try all that life has to offer. To rob my own father. To give all my money away to Gypsies. To make love to four girls at once. To have all my teeth knocked out. To kill whales in the South Seas, to freeze my feet off on Lake Athabasca. To dance myself to death, to burn at the stake for the salvation of all. A thousand seductive things. And if I knew I could resurrect the dead, I would even kill someone – run them through, just once in my life. But instead, I stumble through the mountains as my life forces become slowly spent. Let these secrets remain between us though, my tender-eared brother, they are not truths for everyone’s ears!

On the evening of such feral days, I stink of sweat, I cannot eat for sheer exhaustion, even sleep is long in coming. Once in the Carpathians years ago, I had come to the end of my strength. I could not take another step, so complete was my fatigue. Earlier that day, I had spent hours climbing sheer hillsides without so much as a bite to eat, my heavy pack strapped to my back. Suddenly, I felt my legs turn to lead, lactic acid infused my muscles, and I collapsed. I used to laugh at tales of heroes who, for their wounds or exhaustion, crawled theatrically toward an unattainable aim, only to collapse forever a meter before it. That evening I was no different from them. My pack lay over me, and I could not move. I lay there for a very long time. But those are not the days when a swan appears upon the northern horizon.

Swan days are different. I remember one of them in the Eastern Carpathians. I was alone with three sun-filled, jubilant, weary, feral days behind me. I had not met a soul the entire time. It was the end of September and the shepherds had already led their flocks down into the valleys. After dark on the third day, I descended below the pastures to find shelter beneath a tree. Morning broke foggy and rainy. My back was sore, the weather was dismal and cold. The smoke from the fire stung my eyes, my body was weary from the strain of the previous days and my clothes were damp and sticky. I felt so miserable, I could have cried. But I had to keep going, the rest of my holiday had been planned out precisely. I was suddenly overcome by utter fatigue, more emotional than physical. Another day of lugging myself toward empty and futile goals! On long journeys, ambivalence is dangerous and indecision can be fatal. I stood there blankly. My very being rebelled against leaving, I shook with cold and feebleness. Then I looked up and noticed a black hut standing in the fog. I must have missed it in the dark the evening before. Or had a ghost built it over night? Like Muhammad in his visions, I did not know who was tempting me – was it a good or evil spirit? I drew closer, the hay shed was open. I felt relieved, it was decided. Haste, that wily comrade, vanished and I saw a swan circling above the mountains.

I changed back into dry clothes, and with my sleeping bag, crawled into the darkest corner. Rain drummed on the roof, ancient rain. How sweet to listen to it while lying in dry hay. The first moment of bliss, and how many more awaited me that day! I felt completely and utterly safe, like a child, racked with fever, but cared for by his mother. My classmates were at school, and I lay unconcerned in the uncustomary light of my bedroom, ravaged by illness, yet in safety’s arms, having vivid dreams that are not dreamt at other times. No ill could befall me.

Here, too, walls of wood, hay, darkness, warmth and wafting aromas took motherly care of me. The river of time flowed sweetly by, and its waters took on a new dimension. I lay there for minutes, then hours without moving, the rain drummed, and I sank into the fragrant emerald void. Oh, if death could be so sweet – a crossing into another state of consciousness. Strength vanished, I felt only the boundless yearning to rest. My body yielded to its bed. I lifted my foot, such heavenly exhaustion, a moment later I could no longer even lift a finger. The muscles in my face loosened, their ever-present grimace vanished along with the mask that accompanies people wherever they go. I fell freely into my subconscious. Wonderful imagery arose there, but I had no power or will to capture it. My notebook and pencil were within grasp, but I did not have the strength to reach for them. I was incapable of writing down the thoughts that floated around me that others might experience my joy and assurance, however distantly. Such sublime happiness did not permit me to move, or draw my clumsy hand vacuously across paper. Perhaps later, once the body regains its loathsome, shallow cheerfulness, and the soul reclaims its bothersome busy-bee alacrity which drives a person incessantly and instinctively from nowhere to nowhere. The hours passed silently by, and my soul drank its fill at the wellspring. Such swan days must serve us long, for who knows when they will return again. Without their solitude, the soul would shrivel and dry, becoming like Zarathustra’s empty sacks of flour which might still cloud the air with their dust, but would be of little other use. In those moments, I clearly sensed how most of what people do comes down to mere games and substitution. Everything is a game: work, hobbies, property, art, power. And people – small and self-important. Chubby little toddlers. Of all material necessities, being fed, warm and dry are all we need to survive. And that is all easily attainable.

Sometimes I slept; waking and dreaming merged together. This was no sloth or idleness. It was life to which belong both days of labor and days of rest. I floated in peace and immobility while still clearly realizing all that was going on in the cosmos around me. I lay in the silence of a Carpathian hay shed while one man somewhere shot at another. And throngs of people listened attentively to someone’s speech. And a ship sank into the sea. And billions of spermatozoa surrounded their planet, their earth-like egg. And silent reindeer trekked across the tundra. And a grandmother in Malaysia told her little grandchildren fairytales.

Above the mountains, the day was passing. The hay shed was silent, and I, too, remained quiet and immobile. But life swirled in both of us; we were part of cosmic events. Love and extinction. Tears of joy and realization rolled down my cheeks. I had lain there the whole day without eating or drinking anything, in the dark and the rain. Yet – tears of joy. An old friend of mine told me he had experienced his most profound moments of happiness in a concentration camp during the war. Absolute happiness. And I believe him. The deeper the valley, the higher the mountain, the greater the despair, the more dazzling the exultation. Gratefulness for small things. For all things. If great pain vanishes from the world, so too will great joy. If sin vanishes, so too will forgiveness.

It must have been afternoon, the rain had stopped. The hay shed shone. A fox crossed a corner of the meadow, hunting for voles. It leaped, straight-pawed, into the air, landed, and with a shake of its head went round the other side of the shed. I was beginning my return to the world. The sun was pulling me back. It gleamed through the roof between shingles. My lethargy was dissipating. Thousands of grass seeds and grains of dust danced in the glowing rays, life swirled and turned to gold. As is written in the Vedas, “The sun is the soul of the world.” Fragrant mists rose from the meadows, and the sun awoke amorous fantasies. Pray that the darkest fantasies never come to pass – they would destroy body and soul. I had almost awoken. The swan day had come to an end. I gazed at the evening heavens. Yellow, green, and red clouds scudded swiftly westward. Island-like. Crete, New Guinea, Iceland. Painted monsters. They glided across the, where a high wind blew. How fresh and crisp it must be. To fly with it! Rush with it! How fast would I have to run to feel warm in it? Because the faster I race downhill on a bike or skis, the chillier I feel. And how about a meteor blazing through the air? At what speed do cold and heat meet in perfect balance so the aeronaut can sit astride it in comfort?

The game of the emerald void had come to an end. Night had arrived, the swan had disappeared beyond the horizon, and the day was at its end. A blessed day and a blessed game. Vital and purifying. The wellsprings were replenished, the soul cleansed, the body resurrected. It had revived from its daylong stupor like an Indian saint waking in an underground grave. A moonbeam passed through the roof, piercing the darkness. Silver-gleaming. I suddenly felt my old stallion-strength returning. The yearning to press onwards. I knew that both were wonderful and human: animal strength and clear consciousness. I also knew that the morning after such days would find me once again prepared to bear cold and heat, hunger and thirst, ready to ford treacherous waters, give all my possession to Gypsies, make love to four girls at once, burn at the stake for all of humanity. But let the secret of the emerald void, which breaks time’s reign of terror and snaps the futile whip of haste, remain between us, my tender-eared little brother. That truth is not for all!